India shows the way on globalisation

India has been opening up its markets to foreign investments and creating opportunities for companies globally even as trade wars are closing markets in other countries.

Economists around the world are burning the midnight oil trying to answer the question that is giving sleepless nights to heads of states and C-suite occupants alike: is the world economy heading towards a recession?

Economic report cards from the largest economies don’t make for happy reading. The US manufacturing sector has been slowing for the first time in a decade, China has been growing at the slowest pace in over three decades, the UK seems perched on the edge of a recession, Germany, the world’s fourth largest economy, shrank in the quarter ended June 2019 and in India, the world’s fastest growing large economy, GDP growth rate slumped to 5 per cent, the slowest in over six years (25 quarters).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently cut its global growth forecast for this year to 3.2 per cent, the weakest rate of expansion in 10 years. And more than a third of asset managers surveyed by the Bank of America expect a global recession in the next 12 months.

India bucks the trend by easing FDI norms

Not surprisingly, politicians in many parts of the world are raising tariff walls and increasingly turning insular to try and protect their countries’ economies.

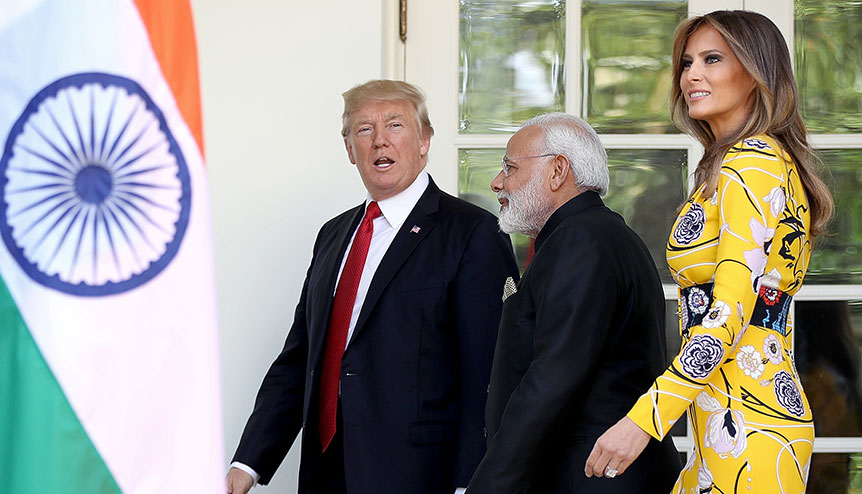

US President Donald Trump set the ball rolling about a year and a half ago by imposing high import tariffs on steep imports from China, India, the EU, Canada and Mexico in pursuit of his “America First” policy.

Since then, the US-China trade war has been grabbing the global headlines but Trump has not spared even allies like the EU, India and others.

Labelling India a “tariff king” he has levied punitive duties on aluminium exports from this country and scrapped benefits India received under the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) regime.

However, India has responded to the rise of protectionism globally by opening itself up much more and by liberalising foreign direct investment norms in a number of hitherto restricted sectors.

Welcoming foreign investments

The Narendra Modi government recently made it easier for foreign investors to enter sectors such as coal mining, single brand retail, insurance intermediaries and contract manufacturing.

The Narendra Modi government recently made it easier for foreign investors to enter sectors such as coal mining, single brand retail, insurance intermediaries and contract manufacturing.

Conscious of the need to proactively step up merchandise exports, which have hovered around the $300-billion mark over the last five to six years, and also cognisant of India’s inability to capture the low-value manufacturing space that China has been steadily vacating, New Delhi has announced big bang steps to attract large contract manufacturers into the country.

This will not only encourage companies such as Hasbro to look at sourcing some of its products from India but also incentivise contract manufacturers such as Foxconn, which makes Apple products in China, step up its investments in India.

Incidentally, India received FDI inflows of $64.37 billion in 2018-19, a new record, but the government has set its sights on attracting annual investments of $100 billion within the next two years.

Welcome mat for US companies

In her Budget speech, Indian Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman explicitly proposed a transparent competitive bidding system for international companies to set up mega-manufacturing plants in sunrise and advanced technology sectors in India. These investors will be provided investment-linked income tax exemptions and other indirect tax benefits, she said.

“I propose to further consolidate the gains in order to make India a more attractive FDI destination: a) The Government will examine suggestions of further opening up of FDI in aviation, media (animation, AVGC) and insurance sectors in consultation with all stakeholders. b)100 per cent foreign direct investment (FDI) will be permitted for insurance intermediaries. c) Local sourcing norms will be eased for FDI in single brand retail sector.”

The easing of FDI norms mentioned above is, thus, a redemption of the above promise. The government has announced that foreign investments will be encouraged in sectors such as semi-conductor fabrication (FAB), solar photo voltaic cells, lithium storage batteries, solar electric charging infrastructure, computer servers and laptops, among others.

Trump’s trade war against China is forcing many multinationals as well as large contract manufacturers to re-order their global supply chains to reduce their dependence on China.

In this context, the US India Strategic Partnership Forum (USISPF), a leading US business advocacy group, has said there is a fantastic opportunity for companies looking for alternatives to China to invest in India.

A report in the Economic Times, India’s leading financial daily, said about 200 US companies are seeking to move their manufacturing bases from China to India.

“We would advise to bring more transparency in the process and to make it more consultative because in the last 12 to 18 months, we are seeing US companies look at some of the decisions being made, either e-commerce or data localisation, as more domestic-oriented than global,” USISPF President Mukesh Aghi told PTI.

“We need to understand how we can attract those companies. And that means all the way from land issues to customs issues to being part of the global supply chain. Those are critical issues. There’s a whole plethora of reforms that need to go further down, and I think that is also going to create a lot of jobs. If you look, our member companies have invested over $50 billion in the last four years,” he added.

Made in India Apple products

The new FDI rules will make it easier for companies such as Foxconn, which manufactures Apple products for the American multinational, to ramp up production of phones and accessories at its factories in India.

Contract manufacturing was a grey area in India’s regulatory scenario. So, the new rules will bring contract manufacturers at par with those companies that set up manufacturing operations for their own products. This is in line with Finance Minister Sitharaman’s Budget announcement on “offering incentives to companies for setting up mega manufacturing plants in… India”.

Absorbing latest technologies, imbibing best practices

The coal sector epitomises much of what is wrong with the Indian economy. The country is the world’s second largest importer of coal despite it having the world’s fifth largest coal reserves. The reason for this is not hard to find: a public sector company, Coal India Ltd (CIL) is the monopoly producer of this mineral in India (steel, power and cement companies, however, are permitted to mine coal for captive purposes).

Recently, the Modi government permitted private players to enter this sector but no private miner has yet entered the field.

By encouraging foreign investors to enter the coal mining sector at a time when the world is turning more protectionist, the Modi government is signalling its intent to allow players with deep pockets and superior technology to challenge the monopoly of Coal India Ltd as well as provide competition to the new private players that will enter the sector.

Single brand retail rules eased

Companies such as Apple, Uniqlo and IKEA will benefit from the relaxation of local sourcing norms for single brand retail and will be able to introduce more products from their global product lines more quickly into India. They will also be able to start selling their products online in India two years before setting up their first brick and mortar establishments in the country.

The policy earlier mandated that single brand retailers source 30 per cent of value of goods sold in India from the country. Under the new norms, all procurements made in India by a single-brand retailer will be counted as local sourcing, regardless of whether the goods are sold in India or exported. Further, such sourcing of goods from India can be done directly by the single-brand retailer or any of its group companies either directly or through a third party.

Getting the timing right

Since Independence, India missed out on several waves of globalisation that drove the integration of East Asia, South East Asia and then China into the world economy.

Since Independence, India missed out on several waves of globalisation that drove the integration of East Asia, South East Asia and then China into the world economy.

Since 1991, however, India has tried to emerge as a global manufacturing hub but without much success. A combination of bureaucratic red tape, poor infrastructure, opaque systems and the absence of sufficient linkages with global supply chains were cited as major hindrances to India’s manufacturing ambitions.

Over the last eighteen months, the Trump administration has imposed three rounds of punitive levies on good worth more than half a trillion dollars imported from China.

The dispute is already showing up in trade figures. Exports of goods and services from China to the US have fallen 12 per cent in the January-May 2019 period.

The US-China trade war, thus, offers India another opportunity to catch up with its Asian peers.

India remains heavily protected

Despite the easing of FDI norms in several sectors and the record inflows of FDI, India still remains among the most heavily protected economies in the world.

An analysis by Mint, a leading Indian financial daily, showed that among the US, the EU, China, Japan and India, the last named has the highest effective rate of tariffs. The Global Trade Alert database shows that the US and India, in that order, introduced the most trade restrictions in 2018.

The latest FDI reforms will help integrate India into the global supply chains of multinationals such as Apple, IKEA, Amazon and a few others but India needs a further easing of norms to attract the likes of other big outsourcers such as Dell, Volkswagen and Alstom, among others.

Then, a record jump of 65 places to the 77th rank in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index, notwithstanding, India remains a very difficult place to do business in. But this is a work in progress and further improvements in both the ranking and the underlying reasons are expected.

Poor infrastructure, high logistics costs, rigid land and labour laws and a complex and adversarial tax system further discourage foreign investors.

Finance Minister Sitharaman has said the government will front load spending on its ambitious five-year $1.4 trillion infrastructure building plan. This will not only provide massive opportunities for Indian and foreign companies to bid for and build infrastructure but also make life easier for businesses that will use the roads, railways, ports and other assets that will be created.

Moving forward with confidence

To be fair to the Indian government, many of the challenges are legacy issues it inherited from its predecessors.

The Modi administration has shown great political resolve in opening up politically sensitive sectors such as coal mining, civil aviation, media and single brand retail to foreign investments, thus, showing an intent to use its political capital to further integrate India into the global economy.

But the intensifying trade war between the US and China, and rising protectionism in its main export markets will not only test India’s preparedness and competitiveness in the world market but also the political will of the Modi government to stay the course on reforming the Indian economy in the face of stiff domestic opposition and global pressure.

A global exemplar of free trade

By swimming against the tide and batting for greater FDI inflows and trade ties, Modi is signalling India’s intent of staying the course on liberalising its economy even as the erstwhile free trade evangelists pull up their drawbridges and retreat to the dubious safety of their isolationist cocoons.

The Indian Finance Minister has promised more reforms in the days to come.